PRB Paintings (The Eight ‘Lights of the World’)

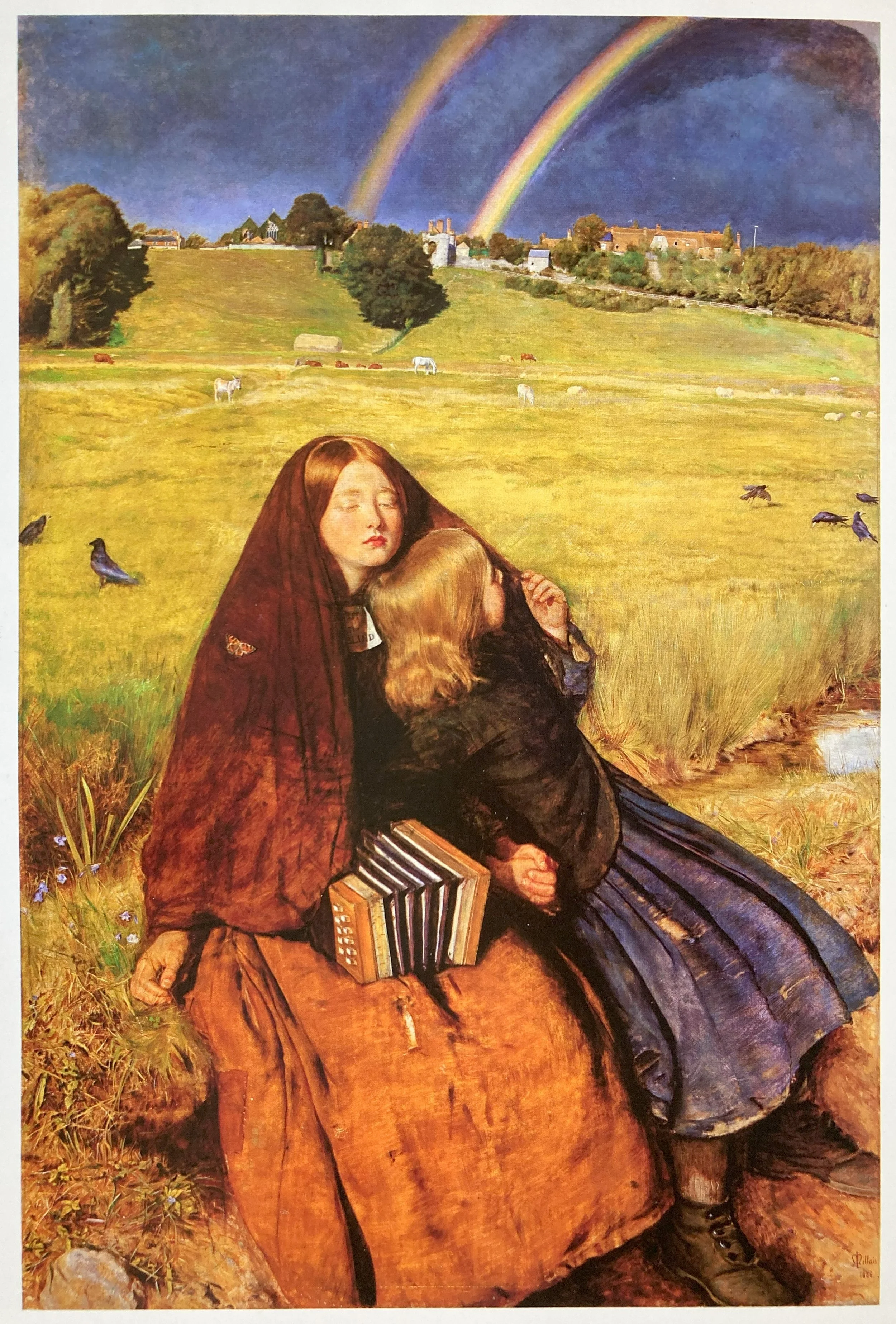

The Blind Girl

(John Everett Millais - 1856) - canvas (81 x 62 cm)

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG)

A blind beggar girl and her companion rest by a roadside stream, waiting for a passing shower to clear. The background is a view of Winchelsea from the east; the two girls - Matilda and Isabella - were local girls from Perth, Scotland, where Millais often stayed with Effie’s [his wife’s] parents. Technically, it is perhaps the most brilliant of all Millais’ Pre-Raphaelite works, especially the landscape with the rainbow and thunder-clouds. Rossetti described it as ‘one of the most touching and perfect things I know’, and Ruskin praised the intensely luminous brilliance of colour, ‘The freshly wet grass is all radiant through and through with the new sunshine; the weeds at the girl’s side as bright as a Byzantine enamel, and inlaid with blue veronica …’

The Awakening Conscience

(William Holman Hunt - 1853) - canvas (74 x 55 cm)

The Tate, London

The first Victorian picture to grapple with the thorny problem [for the time] of prostitution. A kept woman, sitting at the piano with her lover, is suddenly stricken by remorse, and stands up; while the man goes on playing the piano, ignorant of what has happened. Hunt attempted to treat the subject with the utmost seriousness, inscribing one religious quotation on the frame, and two more in the Royal Academy catalogue. This did not prevent the critics from attacking it - the Athenaeum critic wrote that it was ‘drawn from a very dark and repulsive side of domestic life …’; but Ruskin once again came to the rescue, writing a long explanation and defence of the picture in The Times.

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin

(Dante Gabriel Rossetti - 1849) - canvas (83 x 64 cm)

The Tate, London

Rossetti’s first major oil painting, and the first picture to be exhibited with the mysterious initials ‘PRB’. It was begun in 1848 and completed in 1849, with the help of both Ford Maddox Brown and Holman Hunt. The models for the Virgin Mary and her mother were Rossetti’s sister, Christina, and their mother. The picture is full of symbolic references to the life of Christ. Mary Virgin and St. Anne are shown embroidering a lily onto a crimson cloth. Before them stands a lily, symbol of purity, on a pile of books inscribed with the cardinal virtues, beside which there is a child-angel. On the ground lies a seven-leaved palm branch and seven-thorned briar, tied with a scroll inscribed tot dolores gaudia (‘so many sorrows, so many joys’), symbols of the Passion to come. Behind St. Anne is a cross entwined with ivy, a crimson cloak, emblematic of the Robe of Christ, and a haloed dove, symbolic of the Holy Spirit. In the background, St. Joseph prunes a vine, a symbol of the True Vine and Great Sacrifice.

Beata Beatrix

(Dante Gabriel Rossetti - 1864-70) - canvas (86 x 66 cm)

The Tate, London

Painted as a memorial to Rossetti’s wife, Elizabeth Siddal, who died in 1862 from an accidental overdose of Laudanum. Rossetti had in fact begun the picture many years before, but took it up again in 1864 and completed it by 1870. It is one of his most intensely visionary, Symbolist pictures, and marks a new direction in his art. Once again, it represents the death of Beatrice in Dante’s Vita Nuova. Beatrice sits in a death-like trance, while a bird [dove], the messenger of Death, drops a poppy into her hands. In the background the figures of Love, holding her flame, and Dante gaze at each other, with the Ponte Vecchio and the Duomo of Florence silhouetted behind them.

Ophelia

(John Everett Millais - 1852) - canvas (76 x 102 cm)

The Tate, London

One of the outstanding masterpieces of the PRB, combining a Shakespearean subject with a Ruskinian intensity of natural observation. The background was painted in the summer of 1851, on the River Ewell in Surrey. During the winter of 1851-52, Elizabeth Siddal posed for Ophelia, lying fully-dressed in a bath kept warm by means of lamps underneath. Millais purchased an antique dress for her to pose in, and it took him nearly four months to complete the figure. According to William Michael Rossetti, this picture is the best likeness of Elizabeth Siddal ever painted. The idea of painting the mad Ophelia drowning was highly original at the time, although it was to be repeated by many later Pre-Raphaelite artists.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple

(William Holman Hunt - 1854-60) - canvas (86 x 141 cm)

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG)

This was the first major biblical picture to emerge from Hunt’s trip to the Middle East. He began it in the Holy Land in 1854-55, but it was another five years before it was completed. Hunt consulted Dickens about the price, and it was eventually sold to the art dealer, Ernest Gambart, for the enormous sum of £5,500. The picture was a tremendous public success, and the Manchester Guardian wrote that ‘No picture of such extraordinary elaboration has been seen in our day…’

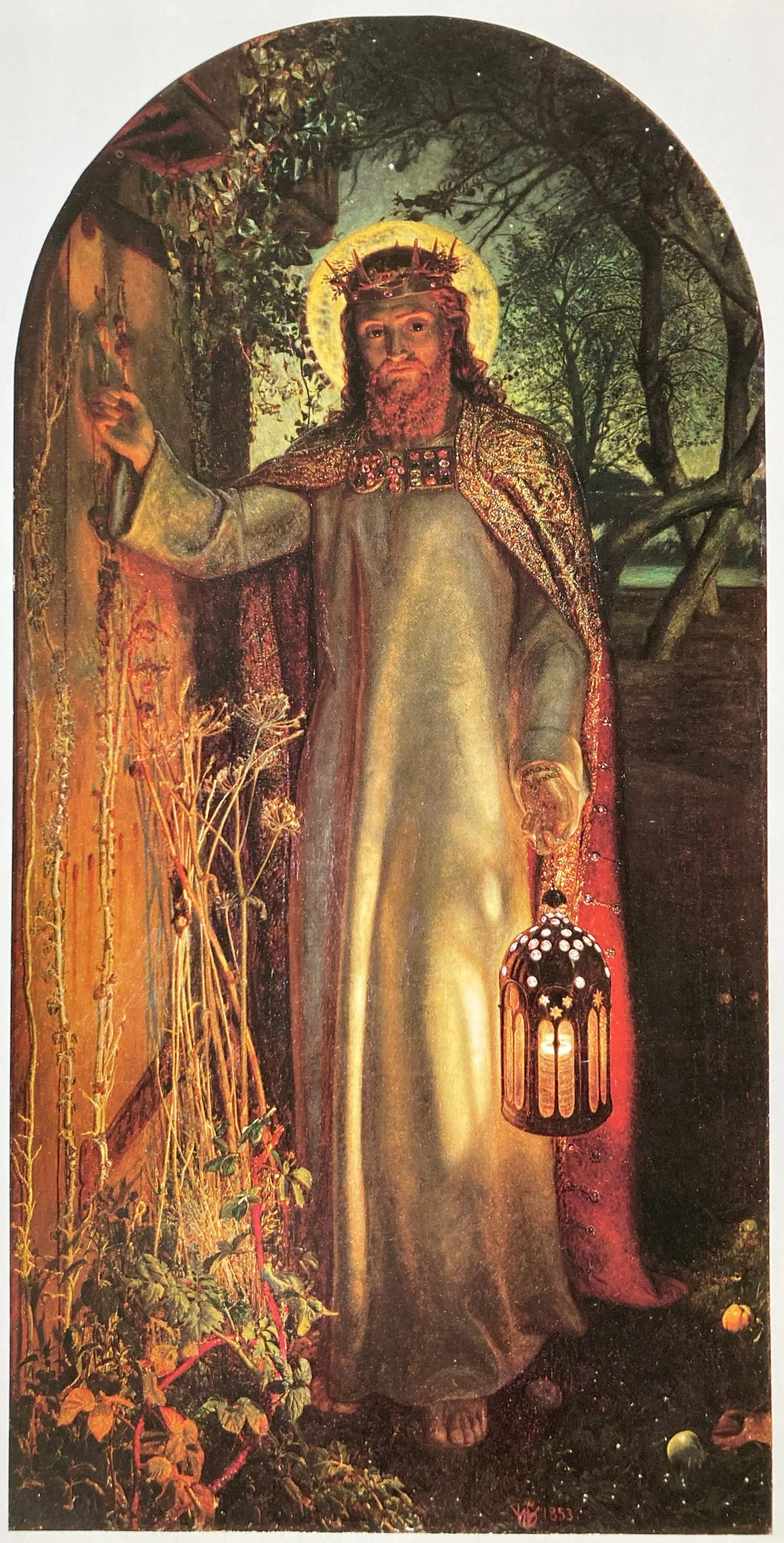

The Light of the World

(William Holman Hunt - 1853) - canvas (125 x 60 cm)

Keble College Chapel, Oxford

Probably the most famous of all Victorian religious images, it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854, together with The Awakening Conscience. It illustrates a passage from Revelations: ‘Behold, I stand at the door, and knock; if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.’ Hunt began the picture at Worcester Park Farm, Surrey, in the winter of 1851, working in an orchard at night. Millais recorded that Hunt was ‘cheerfully working by a lantern from some contorted apple tree trunks, washed with the phosphor light of a perfect moon…’ The picture was not finished until 1853, when it was sold to Thomas Combe of Oxford, who wife later presented it to Keble College. Much later in life, Hunt painted a second, much larger version, which now hangs in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The Gates of Dawn

(Herbert James Draper - 1900) - canvas (198 x 101 cm)

Drapers’ Company, Drapers’ Hall, London

Draper’s iconic image of the Roman goddess of the dawn, Aurora (Eos in Greek), was painted in the last year of the nineteenth century, and heralded the dawning of a brave new world for the Victorians. According to The Globe, it ‘… combined happily a touch of modern ease with the formalities of the Academic manner.’ Draper, usually preferring to paint Greek legends, may have been influenced to paint the model - Florrie Bird - as Aurora, based on the description of Eos from Ovid’s classic poem, Metamorphoses - ‘…far in the crimsoning east, wakeful Dawn threw wide the shining doors of her rose-filled chambers.’ The golden gates she stands by bear discs symbolising the sun, surrounded by medallions of figures representing the planets including Jupiter, Mercury and Venus, together with the winged-head of Time.

Although The Gates of Dawn was shown, and generally well regarded by viewers at the Royal Academy and Walker Art Gallery, The Daily Telegraph and Athenaeum were somewhat critical of Draper’s treatment of Aurora’s left leg. But other writers of the time described the picture as ‘nobly conceived, gorgeous in colour, really magnificent’ and ‘…the most important work in the room.’

Until relatively recently, the painting - presented to the Drapers’ Company in 1929 by Arthur Williams, a cousin of Draper’s wife - had spent decades hanging in a shadowed staircase in Drapers’ Hall. However, a re-evaluation of the picture, as with so many other Victorian works that have generally come back into favour, has seen it rightfully promoted to its current hanging-place in the magnificent Drawing Room at Drapers’ Hall.

Copyright for The Gates of Dawn, to The Masters and Wardens, Drapers’ Company, London.

Sources for the above descriptions include: Simon Toll’s Herbert James Draper, 1863 - 1920, A Life Study; and Christopher Wood’s The Pre-Raphaelites.